Judo and its cousins, Jiujitsu and Aikido, have made much headway into Western culture in terms of sport and philosophy. We’ve incorporated saying such as “if pushed, pull; if pulled, push” and “use your opponent’s energy against them”. Additionally, “xxx jiujitsu” is another form that’s become cliche. For example:

- Marketing jiujitsu—Taking a competitor’s message and flipping it to your advantage.

- Legal jiujitsu—Using a lawsuit or regulation against the party that invoked it.

- Political jiujitsu—Turning an opponent’s attack into a strength or rallying point.

That knowledge only works on those with much less skill. The real art is sensing the subtle flickers—a breath caught, a stray thought, a microsecond of fixation. In that instant, balance is gone and there exists a tipping point of almost effortless opportunity. The throw requires only a nudge—not the power of a 500 lb bench press and 1200 lb leg press. It’s the effortless instant when snow slides off a bamboo leaf.

This phenomenon presents itself in many ways in our lives. The skill of sensitivity to the nuances of state changes should be of fundamental interest to an artificial general intelligence (AGI). How does it manifest in this world where we’re tending more and more towards glossing over subtleties in favor of gross heuristics? In this blog, we’ll discuss this as it manifests in judo (knowledge and skill applied in the physical world), ponder what that capability brings to an artificial intelligence, and to use that as a tool reflecting back on how it is a “level-up” skill.

Large Language Models (LLM), the current focus of AI, is just one piece of the intelligence puzzle. It is a big, important piece of an artificial intelligence, but there are auxiliary “skills” that must complete the picture. Your neocortex is the newest part of our human brain, but it’s also not all there is to human intelligence.

Before continuing, my interest in AI is as an instrument from which to harness insight into our own sentience. After all, the theme of this blog site and fishnu.org is Zen for the Software developer warrior—and AI is software. It’s my hope to demonstrate the wonder of our sentience, not to promote the proliferation of AI.

Finding the Boundaries and the Center

Let’s look at an analogy that ties judo to two machine learning (ML) models that software developers may know:

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Boundary awareness. It tells you how close you are to a decision edge—one tiny step and the state flips.

- K-means: center awareness. It measures how closely a situation matches a template (centroid)—how “throw-ready” the opponent is.

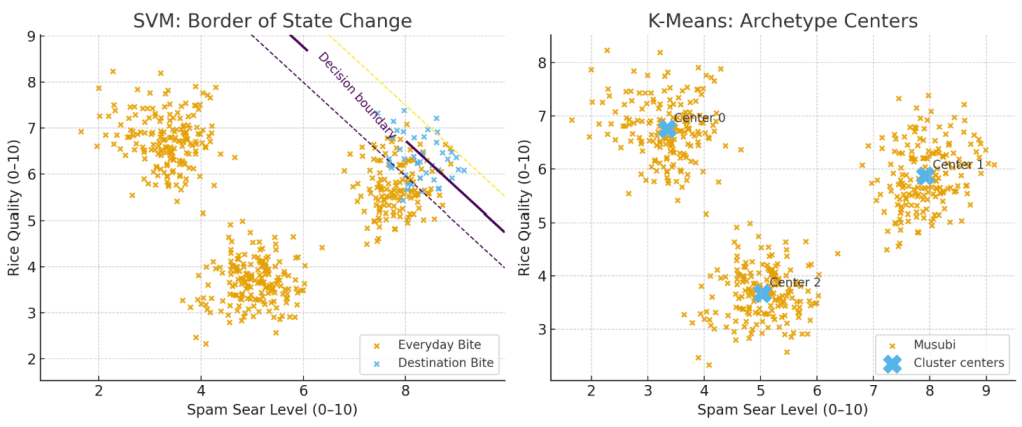

The figure shows a simple example of what these two models look like. It’s Spam Musubi categorization of Spam Musubi on two dimensions—Spam Sear Level (0–10) on the x-axis, Rice Quality (0–10) on the y-axis—through two different lenses.

On the left, the Support Vector Machine (SVM) has drawn a decision boundary between clusters we’ll call Everyday Bites and Destination Bites—two different states of a Spam musubi, the kind that is fine for daily eating versus the kind you travel all the way to Oahu to get. Cross that line and the musubi flips categories. This is like watching the edge of balance in judo—one step too far and you’ve become uke.

On the right, K-means clustering has found the centers of archetypal musubi styles. Each “X” marks the most typical version of a style: the Okazuya Classic, the Grill Master’s Crunch, the Beach Snack. This is like sensing how close your opponent is to a throw-ready template.

Together, the two plots illustrate judo’s rhythm:

- Tsukuri (entry/positioning): Guiding the opponent closer to a centroid, where the conditions for a throw line up.

- Kuzushi (breaking balance): The real moment of change—when closeness peaks and the SVM margin is razor-thin, a small nudge flips the state.

- Kake (execution): The dramatic finish, which looks skillful but is mostly follow-through after the classification has already changed.

SVM and K-means aren’t competing views—they work in parallel. One keeps track of the borders where state changes happen (where we change from participant, to tori, and to uke), the other tells us when the conditions of an archetype conditions are lined up with the many judo throws. Judo—and AI—live in that intersection.

For most of the match you’re both participants. You’re neither tori (the one doing the throwing) nor the uke (the one being thrown). Your states are still open while you’re aware of:

- How close either of you is to a phase-transition boundary where one misstep flips you into uke (that’s SVM).

- How closely your opponent matches a throw-ready template among the many possible throws (that’s K-means).

Now the three-stage throw:

- Tsukuri (entry/positioning): You shape grips, hips, feet—moving the situation toward a throw’s centroid (K-means rising) while staying inside your safe margin (SVM watching).

- Kuzushi (breaking balance): Here’s the subtle truth—this is the actual flip. When closeness to the throw’s archetype peaks, uke’s balance is already gone. The “break” is almost invisible because it’s just a precise nudge delivered at the instant K-means is maximal and the SVM margin is razor-thin.

- Kake (execution): What most spectators think is the big event. But by kake, the classification has already flipped; the finish is skilled-looking yet mostly effortless.

That’s the discipline:

Feel the center forming, guard the edge, and deliver the smallest nudge exactly when the center is true and the margin is nil.

This is how in an instant, the tori can become the uke and vice versa!

AI and Samurai

This is what true focus is. Not a narrow “laser beam focus”, but a field of awareness. Years of training let the body move without calculation. Psychologists might call it “System 1 thinking” (Kahneman), but judoka know it as the natural flow when the mind is free.

The old story of the two samurai makes the same point:

Two masters met at dawn, the village gathered to see an Edo period equivalent of an Ali–Frazier duel. They bowed, drew their swords, and faced each other in silence.

Minutes passed. Neither moved, neither blinked. Their awareness filled the whole field.

At last, they lowered their swords and walked away. The crowd erupted, for they had seen mastery: victory without a blow, focus without fixation.

I used to think that was the stupidest story I ever heard!! That is, until I better understood judo. As Zen priest Takuan wrote:

When you notice the sword, you’ve already lost. By the time your conscious mind realizes what it has seen, it’s too late — the cut has landed.

When your attention has fixated to noticing your opponent’s sword, your attention has collapsed from a field of dynamic flow into a fragmented point of attention. In fact, by the time you’ve noticed your opponent’s sword, a split second (around 200 ms) has passed since it was actually where you’re now seeing it. During that split second, your very worthy opponent had enough time to cut you down.

AI judo, software judo, life judo—it’s the same lesson. Hold the whole field in mind. Then you’ll know where the border lies, when the state is about to change, and how the smallest nudge flip the flow.

Randori, Uchi-komi, and Guitar Chords

In judo practice, there are a few main modes. One is randori—free sparring in a controlled way, improvising against a resisting partner. Another is the more repetitive practicing of the same throw over and over, switching roles (tori and uke) each time. That’s uchi-komi, repetition practice.

When I was a child, I hated uchi-komi—in fact, that’s why I actually hated judo practice. It felt artificial, not like a real fight. But I eventually grew to see it differently. The purpose is not the throw itself, but to train your body to recognize the exact instant—the combination of weight, posture, grip, and balance—when a throw is possible. It’s the instant where the snow slides off the bamboo leaf. Once your body knows that feeling, you don’t have to think. The moment you sense it in randori, you execute naturally.

It’s the same with guitar, which I’ve been learning the past few years. When I was learning a new chord, I learned (from YouTube videos) to place my fingers, lift them a half inch away, and place them back down again. Over and over. The margin for error is so small (like less than a millimeter) that this was the only way to train the fingers to land in the right place instantly.

That’s uchi-komi. Not rehearsal for a “fake” fight, but encoding precision into the body. Repetition teaches the centroid of the archetype — the throw-ready template in K-means terms. Then, in the flow of randori (or a live song), when the margin is razor-thin like an SVM boundary, your body already knows what to do.

Bodhi Day is in three months!

The “secular” Bodhi Day is just three months away—December 8, 2025.

The next Lunar Bodhi Day is January 26, 2026. To calculate Lunar Bodhi Day (8th day of the 12th lunar month) for 2026, I relied on the Chinese lunar calendar for the Yi-Si year, starting Jan 29, 2025, which includes a leap 6th month, as verified by chinesefortunecalendar.com. The 12th lunar month begins on Jan 19, 2026, in China Standard Time (UTC+8), so the 8th day is Jan 26, 2026.

Using Bodhgaya, India (IST, UTC+5:30) as the base—that’s where the Buddha attained enlightenment—I accounted for the 2.5-hour time difference, confirming the lunar day aligns with Jan 26, 2026, in Bodhgaya.

Faith and Patience,

Reverend Dukkha Hanamoku

One thought on “AI Judo: Focus, Edges, and Awareness”