I wrote a book this year. It’s a fairly big book on artificial intelligence. All along, and even after it was published, people told me no one will read such a big book. I agree with them. I usually choose watching a 15 minute video over an hour video on the same subject. Better yet, ten minutes.

Unfortunately for my book, I took on the task of tying a big handful of big subjects into a coherent AI architecture. The publisher of my book thinks no one has attempted that crazy feat. It really did require about 500 pages.

The truth is people will successfully learn what they want to learn, even if it means reading a big, dense 1200-page book (yes, I’m talking to you, Stephen Wolfram). The world today forces us to learn things we don’t really care to learn. We need to learn so many things in order to function in society. So, taking the shortest path makes the most sense. You only need enough to accomplish a task, whether that’s passing a test, or fulfilling some sort of obligation.

But as people tell me every day in my day job, “Correlation doesn’t imply causation”, passing a test doesn’t necessarily imply mastery or even expertise. At best it means you know enough to perform a thoroughly-defined task that someone finds valuable. At worse, you just went through the motions of “studying to the test” because at some point someone decided it has to be done.

Mastery is hard no matter how it’s sliced and diced. As they say, if it were easy, everyone would be doing it. Easy like those tests everyone does pass–at least most people. Mastery is a practice of delayed gratification.

Mastery of something isn’t for everyone. It might be that there isn’t anything you can think of. I always wanted to play guitar, but never so much that I would spend hours practicing during my youth when there were many other things I’d rather be doing. Also, when I was young, there weren’t thousands of free guitar lessons on YouTube, readily available tablatures or almost every song, electronic tuners, etc. Back then, I couldn’t afford a teacher and the nature of my job was such that I couldn’t rely on being able attend a scheduled class.

Four Years of Guitar Learning and Training

Some time around January 2025, I will have been developing my guitar skill for four years. I wrote about this journey and why I started this in my blog, Physical Space in a Virtual World.

After all that time, seriously studying for at least one hour per day, I think I’m still just at “intermediate”. That means if I were in the movie, School of Rock, I could at least play the Angus Young part on the last song (It’s a Long Way to the Top) in the finale. But I’m not quite yet good enough to sit in on my neighbor’s teenage son’s garage band.

But I turned a corner a few weeks ago. They key sign is that I now actually enjoy playing and training. However, enjoying it too much can be a hinderance to progressing since one might tend to do only what they do well. I do mix up my training by selecting songs I sense will offer something new to me, as I’ll soon discuss.

My Lessons Learned

During my guitar journey, I do look at most “tip and trick” videos kindly served up to me by YouTube. You know, clickbait like, “This one trick will make you a rock god”. Many indeed offered good advice, but almost all ended with, “Keep practicing this and you’ll eventually get it.” That sounds like the training of machine learning models—expose the model to a wide variety and large quantity and eventually, it will “get it”.

I kind of don’t like material of the ” Top X best ways to …” genre. It’s counter to the subject of this blog. However, they do have a place—I do read them and find value. So here goes one anyway:

HERE ARE THE THREE TOP THINGS THAT WILL MAKE YOU A GUITAR GOD!

Number 1. By far the best advice was what I just mentioned: Practice every single day, no matter what, even if for just five minutes … which usually turned into a full hour-long practice.

Number 2 is to study music theory. I wrote about this in Music Theory Bodhi Day. Knowing how chords are constructed opens the door to a big toolbox and pulling all the pieces together.

Number 3 is advice from the good Professor, Andrew Huberman. He suggests that after focusing intently on learning a skill (like 15 minute “sets” of focused learning), you should meditate or rest for a minute. This brief pause helps your brain replay and strengthen what you just practiced, reinforcing the learning process. This podcast episode discusses this concept: How to Learn Things Faster. I do note that the title of the podcast contradicts the subject of this blog.

I wasn’t born with the skill of delayed gratification. In fact, this is in some ways the first time in my long life that I’ve built a skill I wasn’t forced to build out of necessity. Most other things like learning to code (which is many times over my 40+ year career every time the new thing came out) was a matter of ensuring I could continue making a living. I do love coding, but learning it once is enough.

One of the first songs I learned was George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord”. As simple as that song is, it includes two awful transitions for a beginner: D to Bm and F# to Bm7. At first I played it a lot, flubbing those transitions almost every time. After almost four years and about a thousand iterations, I suddenly could make those transitions fairly well. So I now only practice it about once a week on “acoustic day”.

The Guitar Gods Saved the “Best” for Last

I was kind of lucky too. I was mercifully unaware of the tougher things I needed to know, which protected me from becoming overwhelmed.

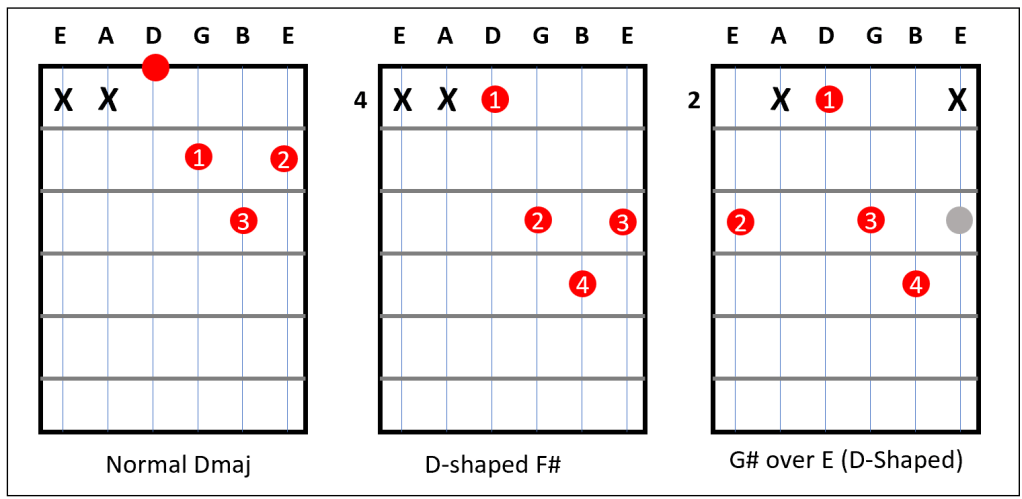

My latest “How did I not know about this?” moment is discovering the “D-shaped bar chords”. A couple of weeks ago, I randomly picked two new songs to learn that sport these chords: BTO’s “Let it Ride” and Rush’s “Spirit of the Radio”. The left of Figure 1 shows the very simple Dmaj chord. Three fingers, no pinky needed, spans only two frets, and the fingers are clustered nice and close but not too tight.

The chord I’m glad I didn’t know when I began four years ago is a “D-shaped F#” chord. It’s F#, but a really convoluted one. You can see the D shape but moved up to the fourth fret. Now, it uses four fingers, including the awkward pinky, and there is a spans four frets.

I originally picked “Let it Ride” to practice the “galloping” part more. It goes on during the ENTIRE verse–versus Heart’s “Baracuda”, where it’s just a few bars.

The right is a rock chord used on Rush’s “Spirit of the Radio”. I decided to tackle that song originally for the arpeggiated riff. But I ran into an awful thing called G# over E. The backbone is a D-shaped E, but the G# bass note adds a really neat classic rock vibe. So, there are two ways I need to learn to play the D-shaped bar chord.

I’ve used this shape mostly in the F# over D form, which is easier (because the D string is open, requiring only three fingers) and appears in many rock songs, such as in Journey and AC/DC songs.

It will probably take a few months before I can do these chords fluently. It’s not so much fingering the chords as it is to transition to them.

Bodhi Season in a Couple of Weeks

Four years to break into the Intermediate range. It might have taken two years if I practiced twice as much as my hour or so per day. It might even have taken just a year if I practiced four times as much. However, I don’t think that logic can continue–for example, six months if I practiced eight time harder … eight hours per day. Probably not, at least for me in the context of my life.

Long ago, I read a martial arts or Zen story that is well-known today. It goes something like:

A student once asked their martial arts instructor, “How long will it take to achieve a black belt if I train every day?”

The instructor replied, “Ten years.”

Determined, the student asked, “But what if I try twice as hard? Train twice as much, stay even more focused?”

The instructor replied, “Then it will take twenty years.”

The student was puzzled, and the instructor explained that true mastery in martial arts (or any art) isn’t just about the hours put in but about the quality and mindfulness of each moment of practice. Overexertion often leads to burnout, tension, or haste, which can obscure growth rather than foster it. Only with patience, a quiet mind, and steady dedication can the student truly progress.

This story reminds us that sometimes, striving too hard for achievement can actually slow our progress, especially in pursuits like Zen and martial arts, where calm and presence are as crucial as physical discipline. I wish I remembered that when I began writing my 2nd book two months ago … but that is a story for another time.

Faith and Patience,

Reverend Dukkha Hanamoku